Rewriting History in a Woman's Handwriting

"When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Brontė who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without singing them, was often a woman."

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One's Own [2]

This collection looks at three examples of nineteenth and early twentieth century literary culture created by and for women. Since the fifteenth century, print culture was—and still is, to an extent—dominated by men and overtly misogynistic narratives. Women were gravely misunderstood and misrepresented, and afforded no opportunities to write themselves into the story. But as time went on, women writers, following a long tradition of women before them, stepped up to challenge conventions.

When women depicted themselves, especially in literature, their narratives were always beholden to a restrictive standard of the mythological domestic woman and her ladylike pursuits. Certain “improper” topics such as political musings and oppressive trauma remained off-limits for women writers for centuries leading up to the modern turn. However, these patriarchal rulings never stopped women from writing candidly, even if publication was a far-fetched, violent sterilization process. To disguise their personal narratives, these women used hidden symbolism in their work, and often went anonymous. Their prolific production of literature, prose, and poetry continuously challenged the ideas tied to the concept of a woman’s proper place and space throughout history.

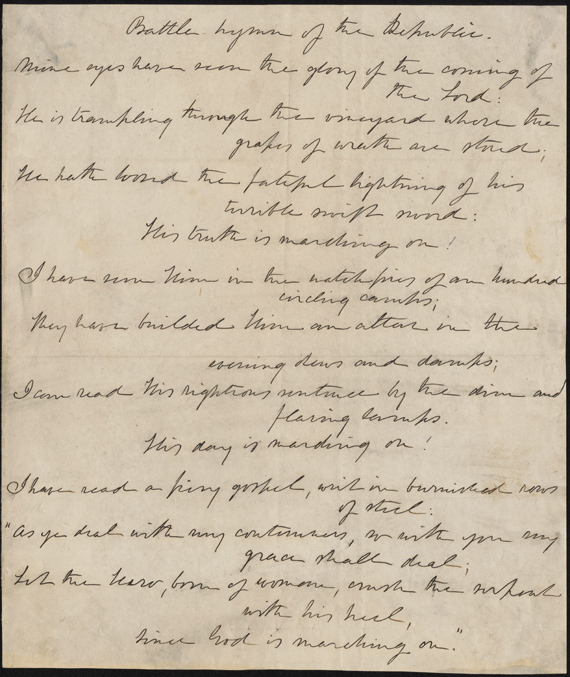

The three items presented here are by two women writers heavily involved in the women’s rights movement, and in the question of anonymity and identity. “Battle Hymn of the Republic” was penned by Julia Ward Howe in the 1860s and published in the popular literary magazine, the Atlantic Monthly. It soon became the patriotic anthem of the North during the Civil War for its inspiring noble militancy, and was endlessly quoted, reworked, and remixed throughout the country and throughout history as a rallying cry for countless other subsequent social causes. However, her name was not printed alongside her work, and it is hard to discern whether she ever was widely credited at all.

She eventually reused her own work, renaming and reprinting it as “Battle Hymn of the Suffragettes” alongside another reworked song entitled “Suffrage Song.” The pamphlet seen here was one mass-printed for use at suffrage rallies, and pointedly includes Howe’s name. With the pamphlet, we present Howe’s handwritten manuscript of “Battle Hymn,” reminding us of her physical presence and agency. Written in her own handwriting, with her own signature at the bottom of the page, a woman’s work cannot be taken from her—even if her name did not travel as far as her work.

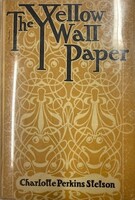

The Yellow Wall Paper has a similar story. Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote this short narrative exploring harmful tropes of feminine hysteria, insanity, and terror. It explicitly shows how silencing and gaslighting women can lead to tragedy and mental trauma—but ironically, it was rejected from the Atlantic Monthly, deemed “miserable” by the editor. Gilman struggled to publish it, but the novella took early feminists by storm in a reclamation of feminine trauma and the need to be heard.

As you explore this collection and the rest of the exhibition, we invite you to consider the power of voice—and silence. How have women used their voices in unconventional ways in order to be heard? Are anonymity and silence always negative things, or is there power in unnamed authorship? What does remaining anonymous mean for these women, and those who came before them?