The Buddha Doesn't Hold a Cigar: Alexander Griswold's Collection at the Johnson Museum

By: Alexandra Dalferro

Note to visitors: This exhibit on Griswold is split into sections that can be accessed through the menu on the left side of the screen.

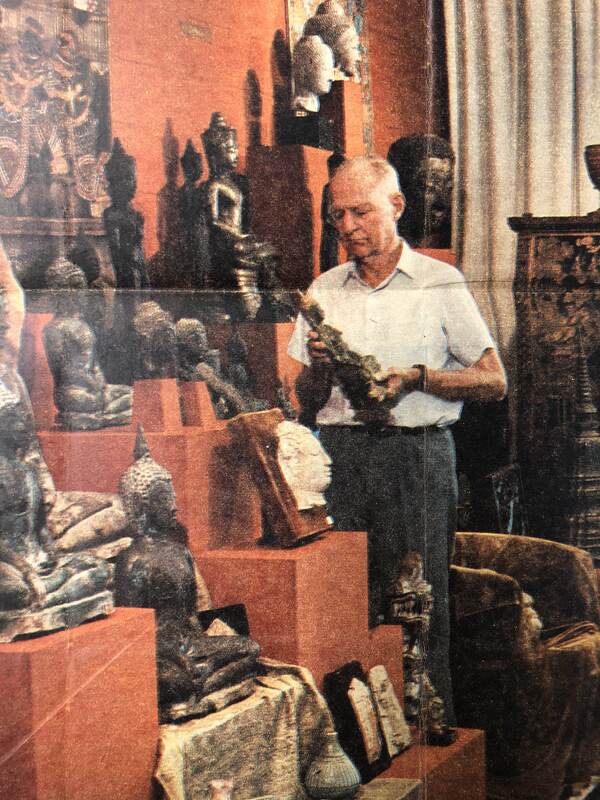

Alexander Brown Griswold (1907-1991) donated 71 objects from Asia to the Johnson Museum beginning in 1975. These objects were previously part of his own collection that he kept at his estate, known as Breezewood, in Monkton, Maryland. Breezewood is a touchstone for generations of Cornell students and faculty, as the name not only refers to Mr. Griswold’s home, but it is also synonymous with his collection and with the seminars that he would hold annually for this group. They are recalled fondly by SEAP community members such as Audrey Kahin, Stanley O’Connor, Craig Reynolds, David K. Wyatt, and others. An excerpt from one of Mr. Griswold’s letters to his friend and collaborator, Gordon H. Luce, offers a glimpse into his schedule and pursuits when he was in Maryland:

My dear Gordon, June 8, 1970

The professors and graduate students from Cornell who attended the seminar have come and gone. They were here for three days, during which time I talked almost incessantly about Siam’s history and art, while they listened with fortitude and apparent attention. A few hours after they left, we had the annual meeting of the Trustees of the Breezewood Foundation, and a dinner party afterwards for the Trustees and their wives. The next day happened to be the first Sunday in the month, so as usual the Breezewood sculpture collection and the gardens are open to the public. Altogether a fairly exhausting four days. Now all is calm again. My learned colleague Dr. Prasert na Nagara and I are settling down again to our epigraphic work. He and his wife have been staying with me for a few weeks, and I have much enjoyed their company. (Griswold papers, #4290)

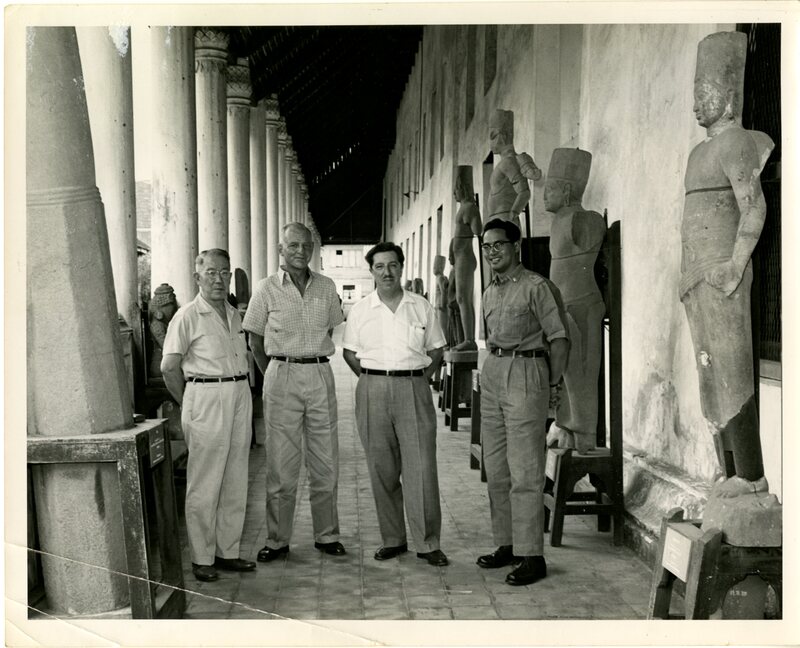

Multiple facets of the character, passions, and milieu of Mr. Griswold are crystallized in this short passage. He was a loyal friend, generous scholar, and devoted patron of the arts of Southeast Asia, especially works of sculpture from today’s Thailand, which he preferred to call Siam, and Cambodia. His interests and achievements were his own, and they were shaped by his background as well as the geopolitical and cultural forces of the period, forces that also propelled the founding of SEAP. Maurizio Peleggi elaborates, “Griswold embodied the Orientalist dimension of the neocolonial relationship that in the second postwar period bonded Thailand to the United States” (2015:79).

Alexander Griswold was born in 1907 in Maryland, attended private schools in Baltimore, and graduated from Princeton University in 1928. He went on to study architecture at Cambridge University, and then returned to Baltimore to join Alex. Brown & Sons, the nation’s oldest investment firm, which was founded by his great-great-grandfather Alexander Brown in 1800. He worked there full-time for ten years until 1939, when the outbreak of World War II forever altered the course of his life by bringing him to Thailand. Griswold served in the army and was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, which charged him and his unit with the liberation of Thailand. He landed in Bangkok in the closing days of the war (Woodward 1997).

In an address at the opening of the Exhibition of Siamese Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art on December 3, 1947, Griswold explains,

If you look at a globe of the earth, you will observe that Baltimore and Bangkok are nearly as widely separated as it is possible for two cities in the world to be. But this geographical separation conceals a certain similarity between the two cities which – however improbable it may seem on the surface, is undeniable to anyone who chooses to look a little more deeply. Baltimore and Bangkok are approximately the same size, approximately the same age, are located in approximately the same relationship to ocean commerce and the interior, and, above all, there are striking similarities in the character of the inhabitants. In Baltimore, though we pride ourselves on our progressiveness, we have a tendency to take life a little more easily than the people of the north; it is the same in Bangkok. We have a certain respect for tradition, and yet a love of laugher; it is the same in Bangkok. Above all. We pride ourselves on the ready friendship offered to strangers, and our easy hospitality: in these respects, I can assure you, from pleasant personal experience, Bangkok has no equal.

These were the reasons, I suppose, that when I first went to Siam in the summer of 1945, and although I was for a considerable time without any American companions, I felt completely at home with the Siamese. The ready friendship and hospitality they offered me were in fact a reflection of the deep devotion of the Siamese people to the Allied cause during the war. In the autumn of 1945, I went to Bangkok, and, through a Siamese friend, I became interested in Siamese art and visited some art dealers and purchased the nucleus of my present collection. Having been honored with the friendship of a number of Siamese, and having noted the similarity of temperament between them and my own fellow-Baltimoreans, I felt at the outset that the objects I was collecting had a kind of personal appropriateness to my own background.

For these reasons, I was to invite you to recognize the objects which we shall see tonight not as the exotic creations of an alien and picturesque civilization, but as the expression of a people who – despite external differences – are not basically dissimilar in temperament from ourselves (Griswold papers, #4290).

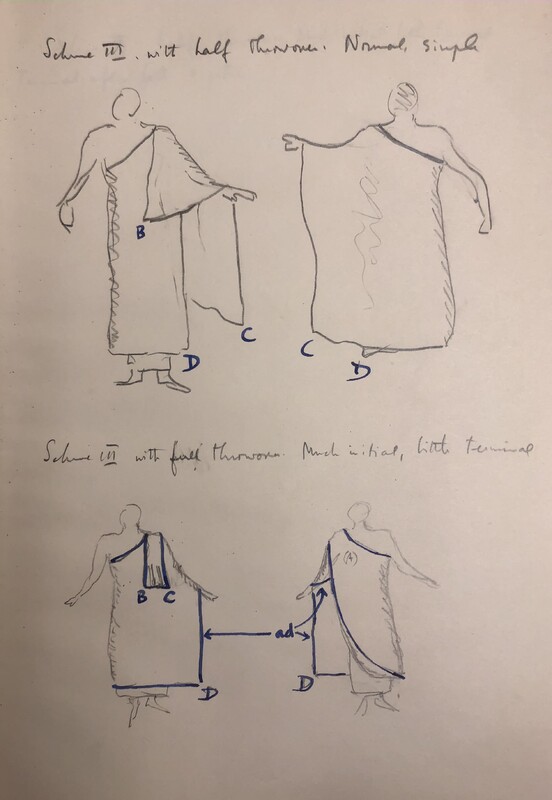

Griswold pleats and folds the earth together to bring Bangkok and Baltimore into relation with one another. His travels between these two centers throughout the course of his life allowed him to gather insights and objects that he integrated into his writings with “meticulous thoroughness” and “exhaustive consideration of all aspects of his subject combined with a clarity of exposition that is seductive to the reader” (Wyatt 1984:13). Griswold’s bibliography is vast, and his style and erudition are epitomized in the important article linking sculptures of the Buddha produced across Asia to historical and contemporary practices of robe-wearing among Buddhist monks (Griswold 1963). Art historian and SEAP faculty member Stan O’Connor included this article in his seminars on Thai art, and Kaja McGowan, art historian, former Cornell graduate student, and current SEAP faculty member in the Department of the History of Art, remembers reading it with excitement. Griswold’s intimacy with both the stone and bronze of ancient sculpture and the materials and rhythms of modern monastic life is expressed succinctly in the following description:

When a [monk’s] garment becomes faded, the monks use vegetable dyes to restore the color. Machine-made cloth, especially when new, falls into rather stiff folds; but I have seen monks in country monasteries wearing homespun cotton, softened by long usage and frequent washing, which falls quite naturally into a profusion of clearly defined and perfectly harmonious pleats (1963:87).

While researching this study, Griswold asked monks across Southeast Asia to demonstrate the ways they achieved these “harmonious pleats” and donned the “Three Garments” that comprise the dress of all Indian Buddha images and are also specified for the Buddhist monkhood in the Vinaya, or the Book of Monastic Discipline. The Three Garments continue to be worn in various configurations by Theravada Buddhist monks today, and as Griswold shows, the arrangement of their pleats and folds is not arbitrary – it is a kind of language that communicates moods and modes of engagement, from “serene tranquility” to “spiritual action” (1963:127). Using photographs of ancient sculptures of Buddha images from China and India; careful line drawings done by Griswold himself of step-by-step processes of robe folding and draping; and detailed visual and textual analysis, Griswold challenges two established conclusions from Western scholarship: firstly, he rejects the idea that the Three Garments have been progressively misunderstood and misrepresented by Buddhist image-makers, resulting in final products that “bear little relation to reality” (ibid:86), and secondly, he refutes the notion that the image-makers were not very interested in dress and simply used it as an opportunity to create spectacular patterns to inspire worshippers. Sculptors rendered “forthright delineation[s]” of monastic dress practices that were familiar to them, and they used drapery as an “exact language” to express significant information (ibid:127). Sculptors knew what they were doing; the folds and pleats they achieved were not incoherent or invented but rather remained close to observable reality and conveyed ideas about the Buddha’s behavior and Buddhist beliefs. Whether worshippers or viewers knew how to “read” this language is a separate question, and Griswold unpacks possibilities so that his audience can begin to comprehend.

One of Griswold’s standing Buddha images that may have assisted in his study of the robes now lives at the Kahin Center on Stewart Avenue, on loan from the Johnson Museum. This bronze Buddha still bears traces of gilding and was created during the fifteenth or sixteenth century in the Ayutthaya period; the Buddha performs the abhaya gesture with his right hand, and his left hand rests at his side. The abhaya position is known in Thai writings as ham yat, or “forbidding the relatives” from fighting when they were arguing over possession of water. An 1879 inscription from Chiang Mai identifies the pose as ham man, or forbidding (or calming) Mara, the demonic celestial king (Woodward 1997). From his position in the alcove of the wood-paneled, bookshelf-lined dining room, this Buddha has helped maintain peace over years of SEAP Thursday Brown Bag/Gatty Lecture lunches, dinners, meetings, coffee hours, conference breaks, and all-night seminar paper writing sessions that this author and her SEAP friends and officemates frequently initiated pre-pandemic. Small offerings are sometimes deposited at the Buddha’s feet, like the bright red plastic cherries, phuang malai flower garland, and candle seen in this photo, and he is always surrounded by the frilly pink petals of plastic blossoms.

Works Cited

Alexander Griswold Papers, #4290. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Griswold, Alexander. "Prolegomena to the Study of the Buddha's Dress in Chinese Sculpture." Part 1. Artibus Asiae 26, no. 2. 1963.

Peleggi, Maurizio. “The Plot of Thai Art History: Buddhist Sculpture and the Myth of National Origins.” in A Sarong for Clio: Essays on the Intellectual and Cultural History of Thailand - Inspired by Craig J. Reynolds. Ed. Maurizio Peleggi. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Woodward, Hiram. The Sacred Sculpture of Thailand: the Alexander B. Griswold Collection, the Walters Art Gallery. Baltimore, Md.: Walters Art Gallery, 1997.

Wyatt, David K. “Alexander B. Griswold and Thai Studies.” Cornell Southeast Asia Program Bulletin. Ithaca: SEAP Publications, 1984.

Explore exhibits: