Yoshie's Gardens

Griswold never married, and he was close with relatives who he mentions regularly in his letters to Luce. In Thailand, he enjoyed entertaining and hosting parties at his riverside home in Thonburi named “Krishnavana House,” which means both “Krishna’s Forest” and “Gris’s World,” the moniker devised by his good friend Prince Chumbhot of Nagara Svarga (Woodward 1997:13). The grounds of this home were filled with arching trees and potted plants, whereas at Breezewood, carefully landscaped gardens surrounded the estate. The gardens were tended by Griswold’s staff and later, by his partner, Yoshie Shinomoto (Landau 2018).

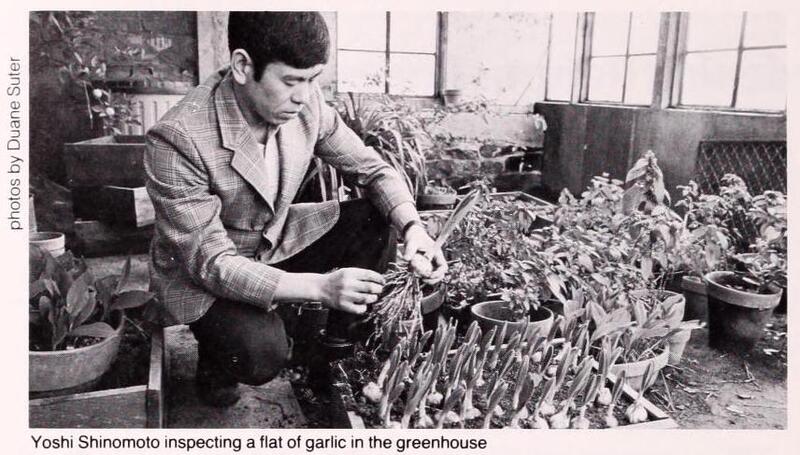

According to a 1981 interview with Yoshie appearing in the gardening magazine Green Scene, Yoshie was born in Tokyo and grew up weeding his family’s vegetable crops. He wasn’t fond of toiling outside in the hot, humid weather, and he preferred to buy his vegetables at the supermarket. Hoping to pursue a career in economics, Yoshie was accepted to the London School of Economics, but he failed the English exam. Later, he gained admission to the University of Michigan and Georgetown University, and mutual friends introduced him to Griswold (Ascher 1981). Griswold invited him to live at Breezewood while he obtained a Master’s degree in linguistics at Georgetown, and he never left (ibid). Yoshie planned and maintained his own section of Griswold’s gardens at Breezewood; grew vegetables like sweet potatoes, eggplants, and onions that he then used in recipes as the house’s main chef; and even self-published a magazine about landscaping. His work is featured in the July 1981 issue of green scene and the April 1983 issue of Architectural Digest with full color photos that convey the care and attention that both men paid to the gardens, but Yoshie is modest, stating, “Without nature, we would not have achieved anything” (Hersey 1983:147).

Griswold’s interest in plants is evident in his writings too; in a 1952 piece he wrote for House & Garden magazine, he describes “monastery gardens” in Siam, detailing his understanding of Theravada Buddhist monks’ relationship with nature and the function of a temple garden as a place of refuge and meditation. One such garden can be glimpsed in one of the works Griswold donated to the Johnson Museum, “The Buddha Preaches in Indra’s Heaven and Descends to Earth,” a painting on cloth made during the late nineteenth century in today’s Thailand that was most likely intended to hang in a temple. In the bottom half of the painting, a temple on earth is depicted, and trees frame its intricate eaves in cloud-like forms, hinting at a garden that may be located behind the ubosot, or the ordination hall. Griswold’s own gardens in Bangkok and Baltimore were likely spaces of refuge for him, too: green expanses where he could walk, think, and appreciate the company of friends and companions like Gordon and Yoshie.

Ascher, Amalie Adler. “Experimental Gardening Returns Runaway Production.” green scene, July 1981, 27-29.

Griswold, Alexander. “Monastery Gardens in Siam.” House & Garden v. 101 Jan-June 1952.

Hersey, Jean. “Gardens: Serenity at Breezewood.” Architectural Digest, April 1983, 142-147.

Landau, Amy. “Looking Forward, Looking Back: Research at the Walters.” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 73, 2018.

Woodward, Hiram W. The Sacred Sculpture of Thailand: the Alexander B. Griswold Collection, the Walters Art Gallery. Baltimore, Md.: Walters Art Gallery, 1997.