Ruth's Pots: The Ceramics Collection of Ruth B. Sharp

By: Alexandra Dalferro

I’ll tell you a story. I’m married; I got married in 1966 and was living in Nova Scotia in 1968. We lived in a small fishing village on the coast of Nova Scotia. I was pregnant with our son, who was due in August. My parents were coming back from a year in Thailand in August. They were going to stop in Halifax and come down and see us. In fact, they were coming on August the 8th, and my son arrived on August the 8th, so nobody could pick them up. We found a friend to go and collect them, but her old Land Rover broke down, and she had to borrow a Bell Telephone repair van, out of which all of the back seats had been removed! There was only the front seat and all the rest was empty, for carrying things. She drove in and my parents arrived. My mother arrived carrying a Vietnamese pot that was a serving platter – it’s a lovely seventeenth century Vietnamese dish. And she had carried it all the way from Bangkok, through the stop in Russia, through the stop in London, and she arrived – and there was this van to pick them up with the person they didn’t know – and my mother gets in the front seat and my father is sitting in the back, and my mother is clutching this bowl, and they arrive at the hospital half an hour after my son was born! And my son now has the bowl at his house. That actually is very descriptive of them. They weren’t super… they weren’t affected about it. They liked the stuff and they liked having it around them.

Suki Starnes told me this story about her mother Ruth and her father Lauriston after I asked her how Ruth lived amidst her collections – whether they were carefully displayed on shelves, or organized in boxes, or used in daily life. As Suki notes, the anecdote is representative of her parents, and especially of Ruth, who was an avid collector of textiles and ceramics and a loving spouse with an intrepid spirit. Ruth perhaps recognized how the spirits of humans, and the passions and pursuits that give life meaning, are shaped by engagements with material things. Ruth’s collections were an intimate part of her world, implicated in her journeys, relationships, and self-making practices.

In 1995, Ruth Sharp donated 182 ceramic objects to the Johnson Museum. She collected them over decades of traveling around the world, especially between Bangkok, Thailand, and Ithaca, New York. Gradually developing deep knowledge of Asian ceramics, Ruth assembled a collection that is used often in classes and regularly displayed on the fifth floor of the museum. Her ceramics enhance the pedagogical and theoretical approaches employed by SEAP faculty members like Kaja McGowan, Stanley O’Connor, Thak Chaloemtiarana, and others who view objects like ceramics as art forms that produce and participate in vast networks of relations. O’Connor elaborates,

[Ceramics] are not employed in these [ritual] contexts merely as neutral containers, as artifacts subsumed in their functions. They are not mere handy crockery but are marked with a potency that makes them active agents. This quality may be inferred to arise from their physical properties, from the hardness, the denseness of their bodies, the smoothness of their surfaces, the ring of their bodies when struck. The aura that surrounds these ceramics seems to have been formed before the age of mechanical reproduction, or it would, in any event, be difficult to think of it developing at a time of limitless availability of cheap, industrially-produced ceramics (1983:403).

McGowan builds from O’Connor’s inquiries to examine the pillaging of ancestral shrines in Bali in the early 1990s. Statues, jewels, and coins were stolen from the shrines and sold, but clay deposit boxes, white cloth, and other raw ingredients were simply thrown away. By looking at what some Balinese people “say and do” about shrines (2008:239), McGowan expands narrow understandings of the shrines and offers crucial reflections on possibilities of more responsible (re)presentation of pieces of shrines in art museums. For example, she proposes that curators display looted statues in one case and juxtapose them with a reconstruction of a demolished ancestral shrine nearby, “making a spectacle of looting and the loss expressed by its victims” (2008:264). She emphasizes,

It is not enough, however, to suggest a decisively Western curatorial response to increase our understanding of Balinese shrines on a global scale. It is also essential to try to divine what might be a Balinese competing practice of explication and a critical reaction to such calamities (ibid).

McGowan’s point here is key, and relates to all objects featured in this exhibit, as they are all “so-called ‘non-Western’ images” that had previous lives in their source communities and now belong to an art museum (2008:263). While exploring local practices of explication are beyond the scope of this exhibit for now, some of the objects’ historical significances and journeys can be established. The objects can also be narrated in inherently partial ways – or in shard-like forms – that leave space for stories to be expanded, added, reworked, and even removed.

Many of Ruth’s ceramics were shaped and fired in kilns located in today’s Vietnam and north and central Thailand beginning approximately in the fourteenth century. The flourishing of ceramics industries in these areas during the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries and possibly later has been attributed to Ming and Qing trade policies, which are categorized as the Ming Ban 1 (1371-1509), Ming Ban 2 (1521-1529), and Qing Ban (1654-1684) (Tai et al 2020). During these periods, production and export of Chinese ceramics were disrupted, and this spurred the production of ceramics in areas that had previously depended on goods from China. Some scholars assert that an influx of Chinese potters into today’s Thailand facilitated ceramic production, while others argue for the greater role of Thai potters in the development of ceramics techniques. Pieces such as this this Sawankhalok vase from Ruth’s collection were produced in Sukothai in the 600 to 800 kiln sites located in and around Sri Satchanalai, and they are prized for their delicate watery hues, or their celadon glaze.

Celadon is a term used for stoneware that has a grayish body and soft green-blue transparent glaze that closely resembles the look and feel of jade. This technique was developed by northern Sung potters with earliest examples dating from the tenth to fourteenth century in Shenxi Province, China. Celadon may have become popular to produce in Sukothai due to the presence of a growing Chinese population in Ayutthaya who desired ceramics in styles familiar to them.

How did Ruth Sharp come to be familiar with these ceramics that were fired in ancient kilns across Southeast Asia? Teasing out these answers requires getting to know Ruth since the moment of her birth. Ruth Burdick was born on June 27, 1910, and she grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and La Grange, Illinois, in a middle-class family. She attended the University of Wisconsin and graduated in 1931 with a BA in history. During college, Ruth had many friends and enjoyed participating in student life activities. She joined the Delta Gamma sorority and regularly attended dances and parties hosted by the sorority and UW fraternities. At one of these gatherings, Ruth met Lauriston Sharp through mutual friends. They became close, and according to family lore, Ruth quickly decided that she wanted to marry Lauri Sharp. She saw in Lauri the prospect of a life of adventure. Suki explains,

My mother was a very, very bright woman. But her main interest in life was being married to my father. My father’s life choice gave my mother exactly what she wanted, which was access to a huge world of international people, international travel, different cultures, meeting different people from all ranks of life; from Thai royalty to Thai peasants. She loved that, and she had it because of my father. They had a lovely marriage.

Ruth’s expansive ambitions were most likely unique among those in her circles, yet Suki’s description of Ruth’s thinking epitomizes the circumstances of many white middle-class women of Ruth’s generation, who conceived of their own possibilities for advancement and self-fulfillment as not only enabled by, but also secondary to, the choices and careers of their husbands. Ruth graduated from UW two years after Lauriston, and moved to Massachusetts to be close to him as he undertook graduate studies in anthropology at Harvard. She taught history at Boston Country Day School, and waited. Lauriston then went to Australia for over two years to do his dissertation fieldwork, and he returned to Massachusetts in 1935. Ruth was still there, still waiting. Perhaps she drank cup after cup of tea or coffee from a similarly elegant vessel like the one depicted below, as she graded papers and indulged daydreams of possible futures with Lauriston, or perhaps her frustration over his reticence could have powered her kettle.

This blue and white cup was made in today’s Vietnam in approximately the fifteenth or sixteenth century. Vietnamese people were the only group in premodern Southeast Asia to use cobalt in ceramic glazes, which stimulated Vietnam’s participation in the international ceramics trade. Ceramics from Vietnam became popular across the islands that today are part of Indonesia and the Philippines, and blue-and-white wares like this cup were produced primarily for export to eager consumers around the world, from Southeast Asia to Japan to the Middle East. In the seventeenth century, Dutch traders purchased 1.4 million pieces of ceramics from Vietnam (Miksic 2009).

In the 1930s, Ruth didn’t yet have any cups or bowls or plates from Vietnam, and she didn’t have a clear sense of the future from Lauriston, either. He completed his PhD in 1936 and pondered over which teaching offer he should accept, and they may have celebrated with glass flutes of champagne, teacups temporarily pushed to the side. Ruth was at her wit’s end. She told Lauriston that if he didn’t marry her, she would wed another suitor instead. Lauri must have appreciated Ruth’s gumption and guts, and he finally came to his senses; the couple married on August 22, 1936, and Lauriston started teaching at Cornell in September. He was soon appointed as the first chairperson of Cornell’s newly created Department of Anthropology and Sociology. His early fieldwork experiences impressed upon him the necessity for cultural anthropologists to be thoroughly grounded in the histories and languages of the people with whom they work. Due to his knowledge of Asia, he was asked to serve as the assistant chief of the Division of Southeast Asia Affairs in the Department of State from 1945 to 1946, and in 1947, Ruth, Lauriston, Suki, and her brother Sander visited Thailand for the first time and stayed for one year.

With support from the Carnegie Corporation, Lauriston initiated the Cornell-Thailand Project in 1947, and most of the project activities were focused on Bang Chan, a rice farming village in Thailand’s Central Plains. Project researchers included Lucien Hanks, Jane Hanks, Hazel M. Hauck, Kamol Janlekha, Herbert Phillips, G. William Skinner, and Robert Textor, who authored groundbreaking studies on topics ranging from internal migration and pedicab drivers (Textor 1961) to the social structure of the Chinese community in Thailand (Skinner 1957). Sharp and Hanks sought to trace shifts in community organization and cultural and technological change as Bang Chan transformed from an “isolated” “rice village” to a town situated on the outskirts of the ever-expanding Bangkok metropolis (Skinner and Kirsch 1975:15; Sharp and Hanks 1978).

When the Sharp family first arrived in Bangkok, they stayed at the Oriental Hotel on the banks of the Chao Phraya River. This hotel is known as the first hotel built in Thailand and opened in 1876; in 1947 when the Sharps arrived, it had recently re-opened through the efforts of six new co-owners after a decade of occupation by Japanese soldiers, followed by liberated Allied prisoners of war. The Sharp family’s room was next to that of Jim Thompson, one of the hotel’s co-owners and ex-OSS agent who had just decided to leave the army to invest in the declining Thai silk industry. Germaine Krull, photographer and former war correspondent, was another co-owner and the manager of the Oriental Hotel. In her memoir, she recalls how she scoured Bangkok for paint to redecorate the dilapidated rooms, finding only “poisonous green” and “unpleasant pink” shades (in Berlingieri 1987:37). She managed to source scarce leather with which to cover large chairs in the lobby and was forced to use both red and blue varieties; enough material of the same color was not available (ibid). The hotel’s own Bamboo Bar was reimagined by Krull with “elegance” in mind; male guests were required to wear ties, and they were provided with them if they arrived without. Krull elaborates, “We made hundreds of ties with the cheapest satin...These ties went round the world as they were collected by visitors and local guests. I bought the most hideous colors I could find. But still, no one objected to wearing a garish orange tie while his partner might be beautifully dressed in pink Thai silk…” (1987:38).

Krull’s apparent aversion to the combinations of bright colors that sometimes characterize Thai aesthetics is difficult to understand when viewing this stunning Bencharong tray from Ruth’s collection. Bencharong, or “five color” wares, were made beginning in the late eighteenth century in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, China. The name comes from Sanskrit terms “panch” (five) and “rong” (color), and relates to the number of colors used on a single piece, although pieces contain between three and eight colors. These ceramics were commissioned by the Siamese/Thai royal family according to their tastes for use in daily life; they held food, tea, water, betel nut remainders, cosmetics, and other substances. They were also used in Buddhist ceremonies. Initially, the court was the exclusive patron of Bencharong, and in the mid-nineteenth century, consumption expanded beyond the royal family and Bencharong became a luxury commodity for Siamese elites (Rooney 2018). Today, Bencharong tea cups with golden fan logos stamped on their bottoms can be purchased at the Oriental Hotel’s gift shop for 6,990 baht each, or $225.00. Another famous hotel in Bangkok, the Dusit Thani, even named its signature restaurant “Benjarong” after these vivid ceramics. Ruth Sharp found them attractive because of “their dazzling colors and jeweled look” (Taylor & Foley 1999:2).

Speaking of neck ties and the relational ties they can manifest, Jim Thompson made this silk tie as a prototype to see if it would be a good potential product – perhaps to replace Krull’s chintzy satin ones – and he gave it to Lauri for Christmas in 1947. Lauriston wore it every Christmas for “many many years – as the wear and tear shows” (Starnes 2020).

The Sharps and Jim Thompson were fast friends. They enjoyed drinking cocktails together at night at the hotel, most likely at the Bamboo Bar, amidst a growing community of American and European professionals who, much like Alexander Griswold, found themselves in Bangkok as they directly, indirectly, and sometimes unwittingly contributed to implementing US imperialist-interventionist and anti-communist policies in the region.

Eventually the Sharps found a house in downtown Bangkok and Lauriston commuted to Bang Chan every day, driving back and forth in a Land Rover. Ruth didn’t accompany him on his fieldwork, and she explained to one SEAP alumna that “they had to find something for me to do” that wouldn’t disturb Lauriston’s work. Another male friend recollected Ruth with fondness: “Ruth was in high heels and fancy dresses while Lauri was in the village.” By accompanying Lauriston and moving with her children to Bangkok, Ruth was doing exactly what was expected and desired of her, and she was most likely in favor of the relocation, too – yet even affectionate memories reveal sharply gendered distinctions that pit serious, masculine research work against flighty feminine fashion and idleness. Ruth would nevertheless defy this division in her own stylish way. Nora Taylor, art historian and SEAP alumna who spent time with Ruth at the Sharp’s home in the 1990s to assist with cataloging her donations of ceramics to the Johnson Museum, affirms,

She was very much a paradox: a woman of her generation, trailing spouse, mother and expatriate society lady and a non-conformist: educated and extremely knowledgeable and eager to learn about the art and culture of Thailand.

Finding something for Ruth to do in Bangkok wasn’t very difficult – she lived next door to Jim Thompson, dubbed by the media as “the king of Thai silk,” and she already loved clothing and textiles. When Ruth was working in Boston during the Great Depression, she wrote letters to her mother in Wisconsin in which she often described her clothing and mentioned the good deals she had found on new pieces. Through Thompson, Ruth began to learn about and collect Thai textiles. They visited silk weaving villages together and engaged in long conversations about collecting and Thompson’s collections. According to Suki, Ruth didn’t view the textiles she accumulated as a “collection” – she was simply buying things that she loved and used in her daily life, from her flamingo pink silk coat that she designed herself, to jewel-toned scarves that she wrapped around her neck or draped throughout her home in Ithaca.

Suki’s observation illuminates two important, interrelated, and persistent ideas about collecting and knowledge production that may have influenced how Ruth viewed certain kinds of material things: first, a group of objects that form a “collection” should have an explicit rationale with tangible intellectual value, and second, textiles and clothing are not worthy of this designation – they are too feminine, domestic, and vernacular. Though Ruth may not have explained her thinking in this way, and if alive today might proudly claim her textiles as a collection, or might still view her silks and batiks and highland people’s garments as too intimate for the academic, museological, distancing language of the collection, these beliefs about collecting, textiles, and clothing still circulate and result in the exclusion of textiles from the “fine arts” museum. Instead, they are more commonly positioned as examples of “material culture,” “craft,” or “costume” in ethnological and natural history museums, where they are implicated in constructing and reinforcing static, timeless ideas about “Otherness” for largely Western audiences. Ruth donated many articles of clothing that were made by, and would have been worn by, members of ethnically minoritized highland groups living in Chiang Mai province, Thailand, to the Department of Anthropology in 1995; none of Ruth’s textiles found their way to the Johnson Museum, though today the museum has an extensive collection of textiles from across Southeast Asia, like the ider-ider. Ellen Avril, the current Chief Curator of Asian Art at the Johnson Museum, must be recognized for expanding the museum’s textile collection due to her remarkable openness and interest in textiles; Ellen was not yet working at the museum when Ruth gifted her highland garments and textiles to the Department of Anthropology. Glimpses of these textiles are included here, and Ruth’s time in northern Thailand in the 1960s and the highland clothing she gathered is explored in sensitive detail in another virtual exhibit, “In Search of Costumes from Many Lands: The Collecting Practices of Beulah Blackmore and Ruth Sharp,” co-curated by Emily Hayflick and Lynda Xepoleas.

Ruth amassed textiles but didn’t “collect” them. Ruth did “collect” “pots,” as she called them – ceramics from across Southeast Asia. Details about how and why Ruth first started seeking out pots are unclear, but Suki relates that Ruth may have been introduced to ceramics through G. William Skinner, who was doing research about Chinese communities in Thailand as a graduate student of Lauriston Sharp. She speculates that Ruth may have first been exposed to Chinese ceramics via Skinner, and her purview then expanded to encompass trade ceramics and ceramics produced across mainland Southeast Asia. Carol Skinner got to know Ruth when her former husband started studying at Cornell, and they also lived in Bangkok at the same time when both of their families moved there to support the work of their scholar husbands. Carol doesn’t recall Ruth ever expressing a strong interest in ceramics when they were in Thailand together, but she remembers Ruth’s sherds and pots laid out carefully at the Sharp’s home in Ithaca. Ruth’s collecting of pots seems to have been an activity that contributed to satisfying her sharp intellect and a way for her to cultivate a legitimate academic interest that was still appropriate for a woman to investigate. Where did Ruth get her pots? Perhaps she browsed the same stalls at the Sanam Luang weekend market described by Ajan Thak, or perhaps like Griswold, she had favorite shops and a network of contacts who would notify her if they had items they thought she would like. In a 1999 SEAP bulletin article about Ruth’s ceramics, Nora Taylor and Jennifer Foley relate, “Acquiring in those days did not necessarily mean purchasing ceramics. It also meant finding them, seeking them out, or hunting them down. In those days, farmers were still digging them out of the fields by accident. She knew where to look for them” (2). Suki confirms that her mother was an “inveterate” shopper – one of her favorite things to do was to visit markets wherever she traveled, especially in Ayutthaya and Sukothai, because she recognized the market as an important social and cultural space and a window into daily life, and she simply loved browsing goods and learning by looking, chatting, and touching.

As she built her collection, Ruth traveled to ancient kiln sites in northern Thailand to see the origins of some of her “pots,” and when she was in Ithaca she even took a class in the Cornell Ceramics Studio to work directly with clay and to make pottery. She complemented this practice-based learning with an academic course on the ceramics of Asia. Taylor and Foley elaborate, “Over the course of the years, Ruth’s collection grew to include hundreds of examples of Thai Sawankhalok ware celadons, Thai Sukothai figurines, Vietnamese blue-and-white boxes and plates, Cambodian Khmer lime pots, and nineteenth-century Bangkok-commissioned, Chinese-made Bencharong ware. But she also has numerous examples of Chinese trade wares: Sung celadons, Ming blue-and-whites, and Swatow wares” (1999:2). When Taylor and Foley asked Ruth about her favorite pieces, she pointed out her Vietnamese frog and a pair of twin Sawankhalok ducks. Both are water droppers dating from the fourteenth century that scholars would have used to add water to their inkwells.

The pieces may have pleased Ruth for their accessibility and whimsicality – they are easy to hold in the hand, and difficult to resist for their familiarity and playful sculpted and painted details. The twin ducks look like they are whispering to each other, exchanging secrets or sweet words, and the opening for water on the frog’s back seems like it has been formed to resemble the center of a delicate flower, the leaves of which drape onto the frog’s body. She collected many similar figurines, droppers, and bottles, like this Thai water buffalo, Thai elephants, Thai weasel or rat, Khmer lime pot in the form of an elephant, and Thai seated woman.

These objects served a range of purposes, from holding substances like lime, which is used in the preparation of betel, to decorating Buddhist temples, perhaps left as small offerings to keep myriad spirits and celestial beings company. At the Sharps’ home in Cayuga Heights, Ithaca, Ruth may have displayed them amidst other ceramics; in 1994, when Nora Taylor visited often to assist Ruth with inventorying her collection, she remembers that Ruth’s pots were all around the house. The best pieces were in the living room on a bookshelf, and lots of sherds were in the bedroom and study. Every time Taylor arrived at the house, Ruth offered her a glass of sherry, ever the consummate host. Carol Skinner remembers Ruth’s sherds and pots filling the house, too, always in view during the frequent dinners and cocktail parties that Ruth hosted as the spouse of an active, esteemed faculty member at Cornell. Though Ruth’s Southeast Asian ceramics were probably not used to serve food at these events, her many plates, dishes, and bowls that are now in the Johnson Museum’s collection evoke festive atmospheres and scenes of sharing meals not only more recently in Ithaca but also thousands of years ago across Southeast Asia.

Imagine eating from this small bowl and discovering the lively daisy upon finishing its contents. Quick, strong brushstrokes render leaves and petals that seem to quiver in a warm spring breeze. The bowl was made in Vietnam in the fourteenth century and is underglazed with iron, which was common before Vietnamese ceramicists adopted blue-and-white techniques that became more popular than this deep brown-black.

If parties at the Sharps’ house lasted late into the night, perhaps extra lighting was required, or maybe bright lights were replaced with softer lamps and candles. This Khmer “jar,” or “pot,” as art historian and ceramics expert Dawn Rooney categorizes it, was made in approximately the late eleventh or early twelfth century at a Khmer kiln.

Scholars establish that Khmer ceramics were not made for export, though pieces have reportedly been found outside the boundaries of the former empire (Rooney 1984). With vigorous and functional shapes, Khmer ceramics were made to be used, and they bear traces of the earth that forms them in their rich brown glazes. The craft of pottery also provided metaphors for Khmer people to reflect on the majesty of the ruling elite; an ancient Khmer inscription dated 647 compares the ruler to the potter’s wheel, constantly in motion and a source of creation (Miksic 2009). Rooney hypothesizes that these flattened globular pots might have served as candle holders, oil lamps, or storage jars for oil, casting light in temples during important religious ceremonies, or helping villagers to navigate dark nights (1984). This pot has simple incised designs around its mouth and body, and the textural richness of such patterns reveals the influence of textiles, with Chinese silks imported by the Khmer court serving as inspiration (ibid). This pot and others like it in Ruth’s collection may have absorbed flickering lights and flashes of silks from their positions on bookshelves at the Sharps’ parties, close to a new center of power and creation.

Ruth not only hosted events in her home but also accompanied and entertained visiting scholars as they descended upon Ithaca for talks and research, such as Margaret Mead, who first visited in 1941 (Lauriston Sharp Papers). Ruth was like a “surrogate mother” or a “den mother” to the newly arrived wives of SEAP faculty member’s male graduate students and recently hired faculty (Skinner 2021), taking them under her wing and teaching them by example what was socially and professionally required of them as “faculty wives.” Ruth demystified this difficult role as she gracefully planned gatherings that could feel “interminable,” but which the archetypal faculty wife must withstand with a smile, sparkling small talk, and a bottomless supply of food and drink, mixed by Stan O’Connor, on-call bartender – Ruth herself enjoyed gimlets. By bringing these women into her life and assuaging their loneliness and confusion, the parties they all attended perhaps occasionally felt less “interminable” and more enjoyable as friendships deepened. The domestic and the professional overlapped and collapsed into one another for women in these positions; Carol Skinner recalls Ruth asking her to come over to help iron Lauriston’s pile of shirts that had to be packed neatly into suitcases in the frenzied final days before the Sharps departed Ithaca for another long stay in Thailand. These forms of invisibilized labor, from ironing to cooking to seemingly-effortless socializing, were crucial in maintaining and furthering the careers of their husbands.

The concept of the “faculty wife” has solidified over time due to persistent gender discrimination and inequities in the American academy; current statistics gathered by the American Association of University Women show that women make up the majority of non-tenure-track lecturers and instructors across institutions, but only 44% percent of tenure-track faculty and 36% of full professors (2021). Women of color are especially underrepresented in college faculty and staff. Female-identified faculty were even rarer when Ruth was an active “faculty wife,” but one key exception was Kaja McGowan, who brought a “faculty husband” into the fold when she became an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History in 1996. Kaja’s spouse, Ketut Raka Nawiana, moved to the US from Bali in the mid-1990s while Kaja was finishing her dissertation and teaching. When he arrived in Ithaca, Ruth and Oliver Wolters helped secure Ketut his first job at Kendal At Ithaca, a retirement community. In Balinese, “Ketut” refers to the fourth child in a family, but Kaja remembers that Oliver and Ruth cheekily called him “Empat” instead – the Indonesian word for “four.” Ruth’s warmth towards Ketut/Empat epitomized the kindness and support she offered SEAP graduate students from Southeast Asia who found themselves far away from the places where they grew up. Perhaps she remembered her early days in Bangkok, when much about the city must have seemed strange and overwhelming to navigate, especially with two small children in tow and a home to set up.

Though Ruth’s pot-seeking activities occupied some of her time in Thailand, she was also an indispensable research assistant, typing Lauriston’s notes and accompanying the Bennington-Cornell Hill Tribes Survey group on their fieldwork trips over a period of eight months from 1963 to 1964, during which time the Sharps were based in Chiang Mai. The dimensions and impacts of this project are covered in detail in the virtual exhibit by Hayflick and Xepoleas mentioned before. Suki asserts that Laurison always encouraged Ruth to write about her interests and to record her extensive knowledge of ceramics and textiles, but didn’t enjoy writing very much – “she did it if she had to.”

Ruth did write a few academic articles about these experiences that were published in the mid-1960s, attesting to her status as a (nontraditional) scholar and researcher in her own right. Two of the pieces focus on Northern Thai craft-making practices and garments of ethically minoritized highland groups, and another essay is titled, “Some archaeological sites in north Thailand,” published in Journal of the Siam Society in 1964. This piece is co-authored by Ruth and Lauriston, but Ruth’s name is listed first, suggesting that she contributed more of the work. Her presence is evident in the article’s attention to ceramics, with rich ethnographic detail on local community members’ contemporary encounters with ancient pottery. At the Yao village of Phale, close to Mae Chan, Chiang Mai, the Sharps report:

From the surface of the Phale village plaza, a quantity of pottery fragments was collected which are quite varied in thickness and color, but which are all unglazed and quite unlike any wares used in Phale today. Village informants reported that in 1961 a European foreigner who spoke some northern Thai visited the village and excavated a large pit in the middle of their plaza from which he removed whole pottery vessels and polished stone implements…Who this farang might be, or what may have happened to his collection, could not be ascertained; but assuming some basis of truth in the Yao statements regarding his finds, it is to be hoped that his interest in the archaeology of the north may lead him to offer some report on this or any other excavating he may have done (230).

They go on to establish,

A considerable local folklore has grown up concerning many of these sites which might well bear sifting and comparison with the places themselves and with early annals of these regions. Much of the archaeological material is in the process of disappearing, and with it will disappear the recollections and traditions of local people which are sometimes most helpful to the archaeologist (231-232).

This anecdote about the marauder farang attests to the widespread looting that occurred across Thailand and Cambodia throughout the decades that the Sharps were in Thailand, and resonates with the dismay over these thefts expressed by Alex Griswold. The Sharps’ investment in the site as academics and researchers is clear; they decry the potential loss of “local folklore” and “recollections and traditions of local people” for archaeologists, but they do not explicitly reflect on how such losses will also impact community members themselves. Their approach is consistent with the times – and with the expectations of a journal like Journal of the Siam Society – when the significances of these sites and memories were still mostly understood through an extractive lens, as an avenue to produce authoritative scholarship. Nevertheless, their acknowledgement that such vernacular, oral ways of knowing are key in developing a deeper understanding of these histories is exceptional, as it indicates that both Ruth and Lauriston Sharp recognized the insights and contributions of villagers to be essential and valid, just as much as they may have valued the interpretations of fellow scholars and experts.

Ruth’s search for antiques and finely-crafted objects did not cease when she left Thailand; they were also propelled by bonds of friendship she cultivated in Ithaca. Ruth and Janet O’Connor, Stan O’Connor’s spouse, loved to hunt for quilts (Janet) and lengths of lace (Ruth) at antique shops and fairs across New York state. Ruth was also drawn to antique plates with hand-painted fruit on them, like plums. Kaja McGowan remembers that they would pack a picnic and spend the day searching for treasures.

Lauriston Sharp passed away at the age of 86 on December 31, 1993 – a November 1993 interview with him by Tamara Loos and Martin Hatch can be viewed here. Ruth eventually moved out of their house in Cayuga Heights to an apartment at Kendal At Ithaca, the retirement community where she helped Ketut find his first job, and she lived there until she passed away on June 16, 2011, just shy of the age of 101. Friends who visited Ruth at Kendal recollect that she kept some of her favorite ceramics with her, mostly small pieces that she displayed in her room. Maybe she brought some jarlets and pots like those pictured here:

This assortment of tiny vessels represents the breadth of Ruth’s collection – with slight favoritism towards Sukothai/Siam/Thailand, where she spent most of her time in Southeast Asia. A jarlet like the mangosteen-shaped form from Vietnam may have reminded her of fruit piled in heaps in local markets and the act of splitting open a deep purple mangosteen shell to reveal glistening white segments with technicolor flavor; the Bencharong jar and the Sukothai jar recalling early memories of Bangkok and the thrill of pot-hunting; and the Khmer vase shaped like a gourd, which Dawn Rooney speculates may be a bottle for holding liquid like rice wine, or incense, eliciting flashes of smoky rooms crowded with people enjoying one another’s company at parties in Bangkok and in Ithaca. This gourd symbolizes longevity and immortality, qualities that are fitting when speaking of Ruth, as her indomitable spirit and passions are carried into the future through her pots.

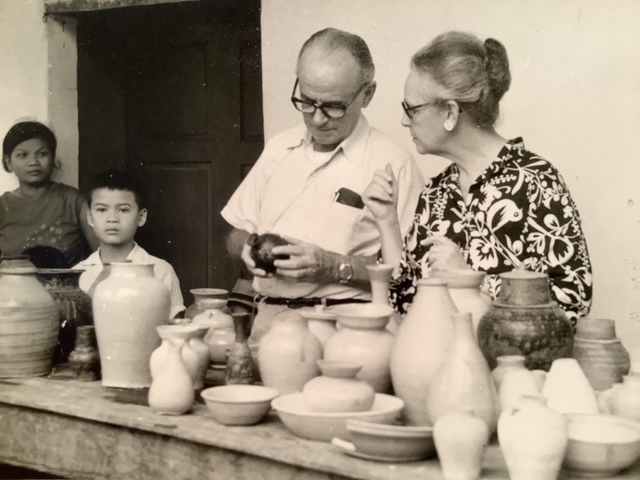

Ruth and Lauriston in Ithaca; Ruth is wearing a skirt she designed herself with a hem that is made from a piece of a woven textile that she bought in Thailand.

Works Cited

Berlingieri, Georgio. An Oriental Album: A Collection of Pictures and Stories of and about the Oldest Hotel in Thailand. New York: DK Book House, 1987.

“Fast Facts: Women Working in Academia.” American Association of University Women. Accessed 30 March 2021. https://www.aauw.org/resources/article/fast-facts-academia/

Lauriston Sharp Papers, #14-25-2618. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

McGowan, Kaja. “Raw Ingredients and Deposit Boxes in Balinese Sanctuaries: A Congruence of Obsessions.” In What’s the Use of Art?: Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, Eds. Jan Mrazek & Morgan Pitelka. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008. 238-271.

Miksic, John. “Kilns of Southeast Asia,” in Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery, ed. John Miksic. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2009. 49-69.

O’Connor, Stanley J. Personal interview. 26 October 2020.

O’Connor, Stanley J. “Art Critics, Connoisseurs, and Collectors in the Southeast Asian Rain Forest: A Study in Cross-Cultural Art Theory.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 14(2): 1983, 400-408.

Rooney, Dawn. Oxford in Asia Studies in Ceramics: Khmer Ceramics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

---------. Bencharong: Chinese Porcelain for Siam. Bangkok: River Books, 2018.

Sharp, Lauriston and Lucien Hanks. Bang Chan Social History of a Rural Community in Thailand. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Skinner, Carol. Personal Interview. 5 February 2021.

Skinner, G. William and A. Thomas Kirsch. Change and Persistence in Thai Society: Essays in Honor of Lauriston Sharp. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975.

Skinner, G. William. Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1957.

Starnes, Suki. Personal Interview. 2 December 2020.

Tai, Yew Seng, et al. “The impact of Ming and Qing dynasty maritime bans on trade ceramics recovered from coastal settlements in northern Sumatra, Indonesia.” Archaeological Research in Asia, 21: 2020. 1-18.

Taylor, Nora. “Re: A Sharp Eye: Ruth Sharp,” Email communication. Received by Alexandra Dalferro, 27 October 2020.

Taylor, Nora & Jennifer Foley. “A Sharp Eye: The Ruth B. Sharp* Collection of Southeast Asian Ceramics at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University.” Cornell Southeast Asia Program Bulletin, Spring 1999. 2-5.

Textor, Robert B. From Peasant to Pedicab Driver: A Social Study of Northeastern Thai Farmers Who Periodically Migrated to Bangkok and Became Pedicab Drivers. New Haven: Yale University, Southeast Asia Studies, 1961.

Xepoleas, Lynda & Emily Hayflick. “In Search of Costumes from Many Lands: The Collecting Practices of Beulah Blackmore and Ruth Sharp.” Virtual Exhibit, Cornell University, 2020. https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/in-search-of-costumes-from-many-lands