Shadowlines

By: Anissa Rahadi

“To sum it up, one night does not suffice. … The characterization is incomplete – there are too many shades.”

(Quoted from Tjan Tjoe Siem, who quoted the “Venerable Dalang” about the richness and expansiveness of the wayang world, Holt 1967, 123)

Note to visitors: This exhibit on Griswold is split into sections that can be accessed through the menu on the left side of the screen.

Wayang is a polysemy. It designates the performance of wayang kulit (of puppets made of flat, carved leather, and buffalo horn) – the shadow play – as Holt reveals in her opening sentence as the heart of the wayang world. Wayang, in its broadest sense, is an over-encompassing dramatic performing art across Java and Bali. It has its world system that reflects the artistic penchants of the Javanese and Balinese and their religious mythology, metaphysics, ethics, and relationships to the natural and supernatural order. Wayang stories could also be performed with golek (wayang golek) or puppets made from carved wood and wong (wayang wong) or wayang played by human beings.

This part of the exhibit explores the connection between scholars and objects and between collecting and teaching. Shadowlines presents these wayang objects as a way to trace the genealogy and history of Indonesian Studies at Cornell, starting from objects donated by Claire Holt through Benedict Anderson, to Ben’s collection, and more recent acquisition from Joseph Fischer and Martin and Susan Hatch. Many of these objects occupy a vital position in the current teachings on Southeast Asian art by Kaja McGowan. The puppets are also used in shadowplay performances by Javanese and Balinese dalangs invited by the Southeast Asia Program to perform short lakons (stories) at the Johnson Museum accompanied by the Cornell Gamelan Ensemble.

The beginning of the wayang tradition in Java is unknown, although the Hindu epics of the Ramayana and Mahabharata had been adopted since at least the first millennium (Sears 1984). However, only in the tenth and eleventh centuries were the wayang play recorded in Javanese inscriptions and manuscripts. The stories in wayang play continued to evolve throughout centuries as dalangs (shadow puppeteers) play different lakons (stories) from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, develop local stories, and incorporate Islamic narratives, such as the Amir Hamzah written in the Javanese manuscript of Serat Menak. In addition, there are also many wayang stories from the Hindu epics that show the transition from Hindu-Buddhism to Islam. Many Indonesian scholars and dalangs attributed stories that reflect Islamic values, such as Dewa Ruci, Jimat Kalimasada, Petruk Dadi Ratu, Semar Mbarang Jantur, Wahyu Widayat, and several others, to the figures of the venerated Wali Sanga (The Nine Saints) of Java, notably Sunan Kalijaga and Sunan Gunung Jati (Maharsiworo 2013, 62; Sofwan 2000, 157-8). Wali Sanga are semi-historical figures who spread Islam in Java in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries

One of the wayang objects in the Johnson collection that visibly shows Islamic influence is the Shadow puppet representing Bouraq. Bouraq or the Buraq is a semi-mythical composite being of half-human and half-quadruped animal – the company of the Prophet Muhammad in his miraculous night journey known as the isra and mi’raj in Islamic narratives. Isra and mi’raj refer to the Prophet’s journey riding the Buraq, who transported him with a speed of lightning from Mecca to Jerusalem and from Jerusalem to the seventh level of heaven to meet with God in a single night. As shown by the puppet, the Buraq is depicted with the head of a beautiful woman with flowing hair and a crown in a naturalistic manner, unlike most stylized representations of the shadow puppet characters in Javanese and Balinese wayang pantheons. Considering the naturalistic representation, it is possible that the dalang who made it copied it from the representations of the Buraq in South Asian visual traditions that might have spread into the Indo-Malay archipelago through printed materials, such as posters or calendars. It is also possible that the Bouraq came from the same dalang who made numerous representations of shadow puppet animals based on the similarity in the rather naturalist depictions of the animals. In the world of the wayang, this shadow puppet representing the Buraq might be used in stories related to the propagation of Islam in Java.

Wayang and the Southeast Asia Program at the Johnson Museum

The fascination with wayang and the shadow world filled and shaped the imagination about Java and Indonesia. Wayang was always prominently featured in international events promoting the refined arts and culture of Indonesia. Many foreign scholars who worked in Indonesia, including Claire Holt, fell in love with the performance during their time in Java and Bali. Many of these scholars eventually began commissioning and buying puppets from local makers as gifts, personal collections, and in the case of Claire Holt, research materials for her monograph, Art in Indonesia: Continuities and Change (1967). In February 1981, Claire Holt’s wayang kulit collection made its initial appearance in Ithaca in a special exhibition at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum. Organized by Susan Shedd from the museum, Shadow World of Javanese Puppets featured thirty-six puppets of wayang kulit purwa – the ‘original’ repertory drawn from four groups of myths including the Indian epics of Mahabharata and Ramayana – and wayang gedog – wayang playing the repertory from East Java stories, such as Panji – as well as other major and minor characters from both traditions. At Cornell, the Southeast Asia Program hosted a lunchtime talk about Java at 102 West Avenue by anthropologist Ward Keeler to accompany the exhibit. Mediated through Benedict R. O’G. Anderson (Ben Anderson) and the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project (CMIP), the puppets soon came into the museum’s permanent collection. They marked the first group of wayang puppets that added to the strength and richness of Southeast Asia at Cornell and the Johnson Museum.

The first inhabitants of the shadow world at the museum include main noble characters from the Mahabharata, the five brothers of the Pandawas: Yudhistira, Bima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sadewa, well as several characters from Ramayana, and minor characters in Javanese and Balinese shadow plays. Out of the five Pandawa brothers, Arjuna is the most popular, and it is reflected in the presence of several Arjuna types in the collection, such as Arjuna Sepuh (Arjuna when old) and Arjuna Permadi (Arjuna when “good looking”). In the world of shadow play, Arjuna is an epitome of a whole man, a complicated yet loved character filled with reconcilable contradictions. He is, as Ben Anderson writes in his monograph Mythology and the Tolerance of the Javanese (1965), an “… unequaled warrior on the battlefield, yet physically delicate and beautiful as a girl, tender-hearted yet iron-willed, a hero whose wives and mistresses are legion yet who is capable of the most extreme discipline and self-denial, a satrya with a deep feeling for family loyalty who yet forces himself to kill his half-brother” (25). His adventures to find love fascinate and delight many Indonesians even until today, as shown in numerous adaptations of Arjuna in modern popular cultures in Indonesia.

Claire Holt’s research and personal interests in Javanese and Balinese wayang passed on to her student, Ben Anderson, who worked on Indonesia for his dissertation project in political science and government studies under George Kahin. During his graduate year, Ben wrote Mythology and the Tolerance of the Javanese – an exploratory book on the shadow play outside of the context of performing arts. In this book, Ben looked at the world of shadow puppets in Java as a reflection of the sociological and psychological conditions of the Javanese. By utilizing the illustrations of wayang kulit derived from J. Kats’ Javaansche Toneel I: Wajang Purwa (Javanese Performing Arts: Wajang Purwa) published in 1923 and Hardjowirogo Sedjarah Wajang Purwa (History of Wayang Purwa) published in 1955, Ben catalogs the major and minor characters involved mainly in the epics of Mahabharata and Ramayana, such as the Pandawas and their fated rivals and enemies, the Kurawas.

While the shadow world often shows the universe that can be easily divided into ‘good’ forces and ‘bad’ forces, dark and light, left and right, young and old, and so forth, Ben asserted that the world is filled with complexity, ambiguity, and sliding scales of morality. As noted by Ben (1965, 17), these divisions and dualities are not absolute. It depends whether one watches the puppets or their shadows on the other side of the kelir (wayang screen), “… right becomes left and left right. Both are merely in the eye of the beholder.” For the Javanese audience, the moral ambiguities in the stories of wayang could turn into an endless discussion about appropriateness and become a way to impart a sense of duty, honor, piety, and courage that are tied to the hierarchy of castes in Javanese and Balinese world.

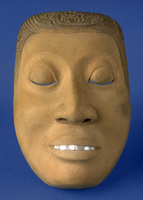

Even though Ben had conducted extensive research about wayang and had saved Claire Holt’s puppets collection before he gifted them to the museum, when it comes to his desire for things to collect, Ben fell in love instead with topeng (masks). His collection of masks, along with a few more of Claire Holt’s wayang golek puppets, such as the one that represents Kuraisin or a princess, came to the museum in 1998. Together with the museum’s recent gifts that year from Cornell professors and alumni, they were exhibited in an exhibition titled Traditional Arts of Indonesia, Burma, and Thailand. Ben acquired many of his masks during his two and a half year stay in Java from 1962-1964, conducting research in many areas of Java and visiting flea markets in provincial towns like Malang, Cirebon, Solo, and Semarang. Ben’s interest in Javanese and Cirebonese masks emerged after reading Th. Piegaud’s Javaansche Volksvertoningen (1938) to teach himself the Dutch language for his fieldwork. “Nothing among the book’s many illustrations so entranced my eyes as the photographs of masks and masked performances,” Ben reminisced in his collector’s notes published in the SEAP Bulletin in Spring 1999. Ben acquired many masks from the local flea markets and from itinerant dealers who heard through the grapevine about him looking to buy masks. For that reason, there is no particular justification why Ben chose the masks he chose. However, he made sure that there are good representations of the styles in East Java, Central Java, Sundanese, and his personal favorite, “… the unearthly uncanniness of Cirebon.”

One of the masks that deserves a special note is the refined Dalem mask carved by one of the most prolific Balinese painters, Ida Bagus Made (1915-1999), and gifted to Ben a few days before they parted in 1967. Ben wrote that Ida Bagus Made made the mask specifically as an art object rather than for performance. He deliberately left the mask unpainted and exposed the carved wooden texture. Amongst the painted masks from Java in Ben’s collection, this Dalem mask certainly stands out. The mask was carved exquisitely from softwood and had a smooth texture and plasticity as if it were molded out of clay. From conversations with Ben about the mask for an article The House that SEAP Built in the Fall 2020 SEAP Bulletin, Kaja McGowan recounts Ben’s concern about the mask losing its taksu (power) as it had lost one of its mother-of-pearl inlaid teeth soon after it had arrived in the US. Kaja offered to fix the tooth using her collection of square buttons from Muscatine, Iowa, carved out of freshwater mollusks in the 1920s. Not only this mask shows Ben’s journey and the relationship he built in Indonesia, but it also physically incorporates the new relationship with SEAP younger faculties like Kaja, who helped acquire Ben’s masks for the museum to support her teaching on the arts of Southeast Asia.

Through Kaja McGowan, the Johnson Museum also acquired a large quantity of wayang kulit puppets from a scholar of Indonesia, Joseph Fischer. Fischer is known for his publications on Indonesian folk art: Threads of Tradition: Textiles from Indonesia (1979), The Folk Art of Java (1994), and The Folk Art of Bali (1998). While Joseph Fischer was not officially affiliated with SEAP and Cornell as he worked at the University of California, Berkeley, his wife’s family had a connection to Cornell. He entrusted his collection to the museum, knowing that they will support teaching and learning about Indonesia and Southeast Asia at Cornell.

The acquisition of objects from Joseph Fischer started with the exhibition of The Story Cloths of Bali in 2006, which displayed textiles made by women from the Jembrana and Buleleng districts of Bali that mainly narrate stories drawn from the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The story cloths came to the museum’s collection in 2008 as a partial purchase/partial gift from Fischer. As he wished to keep the story cloths and his shadow puppets’ collection together, the museum acquired many of Fischer’s wayang kulit through the George and Mary Rockwell Fund. While Fischer identified the most valuable and brilliantly executed puppets are the ones representing gunungan and Batara Guru (Siwa) from Java, and those from the Calonarang story from Bali, his collection of female characters from different lakons (stories) in Mahabharata, Ramayana, and local stories, is arguably the most important addition. Durga, Rokmini, Sita, Arimbi, Anjani, and Limbok and Mem Brayut from Balinese popular folk tales from Joseph Fischer filled the lack of female characters in the previous collection that came from Claire Holt and Ben Anderson.

The most current donation of wayang objects came from Martin and Susan Hatch a year after Fischer’s acquisition. Martin Hatch is an emeritus professor in the Music Department who started the Cornell Gamelan Ensemble in 1972 as he began his graduate training in the Music Department supported by the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project. According to Marty, when he arrived at Cornell in 1972, there was already an ensemble-sized gamelan group where Ben Anderson was a central figure. During his multiple trips to Indonesia, Marty collected various objects, including Balinese paintings, Javanese statuettes, and golek puppets he commissioned in Yogyakarta. Twelve of Marty’s golek puppets made their way to the museum collection as Marty never intended to keep them at home. His golek donation added to the small number of puppets previously gifted by Claire Holt through Ben Anderson that also came from Central Java. Many of the goleks Marty gifted are character types meant to represent non-specific figures, such as the wayang golek representing an Arab, a nobleman, or a princess. Marty also included the members of the punakawan (clown figures), the children of the god-clown Semar, such as Petruk and Gareng.

While Ben Anderson was concerned with the puppets and masks losing their performative essence when entering a museum – and that might be when ritual objects like wayang and masks lose their devotional function – they are reanimated in different ways when used in classroom teachings or when they were reawakened through wayang performances at the museum. In Fall 2019, Kaja McGowan taught a seminar that highlighted the shadow puppet objects at the museum. This class was held in conjunction with a visit and residency of Gusti Sudarta, a well-known Balinese puppeteer (dalang), and Darsono Hadirahardjo, a Javanese musician and dalang. The class introduced students to wayang stories and characters, looking into the roles, significance, and transmission of the shadow performances in Southeast Asia, particularly in Java and Bali. In a class with Sudarta, students made puppets of various animal forms from cut papers and wooden sticks – some were painted, some left bare. In November 2019, the class attended two wayang performances by Gusti Sudarta and Darsono as the dalang, accompanied by Cornell Gamelan Ensemble. These dalangs were also involved in SEAP Outreach Programs, introducing wayang to communities outside of Cornell. These visiting dalangs, as Kaja McGowan asserts, bring back the performative aspect of the shadow puppets at the Johnson Museum.

The history of the Southeast Asia Program and its focus on Indonesian arts and culture is reflected through the collection of wayang puppets collected by SEAP’s leading scholars. These objects came to the Johnson Museum collection and played an important role in teachings and outreach programs. They became part of the strength of the Southeast Asia Program at Cornell and the Johnson Museum.

Works Cited:

Benedict Anderson papers, #14-27-4189. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Anderson, Benedict. Mythology and Tolerance of the Javanese. Ithaca, New York: Modern Indonesia Project, Southeast Asia Program, 1965.

Anderson, Benedict. “A Language Learned in Java: A Collector’s View of His Masks.” SEAP Bulletin, Spring 1999.

Holt, Claire. Art in Indonesia: Continuities and Change. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1967.

Maharsiworo, K.R.T. Sunardi. “Islam in the Javanese Cultural Pluralism and the Keraton Performing Arts.” Al-Albab: Borneo Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2013.

Sofwan, Ririn. Islamisasi di Jawa. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar, 2000.